Spiraling Forces Reveal the Essential in Nature and Art

This week, as the latest hurricane barreled across Florida, a friend reached out to share with me an interview actor Andrew Garfield gave to the New York Times addressing the question: why is art so important?

Tearfully, he replied: “because art can get us to places that we can’t get to any other way.”

This assemblage by Puerto Rican artist Daniel Lind-Ramos (b. 1953), Baño de María (2018-2022), in the permanent collection of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, contains coconuts, musical instruments, and FEMA disaster relief tarps.

This rings absolutely true to me, even as I’ve always loved to travel by pretty much any mode of conveyance.

Yet after leaving behind careers in diplomacy and international business over eight years ago, I made the powerful discovery that art can take me even more places than a car, train, or airplane.

I still travel frequently, as I build relationships with collectors, galleries, and professionals, for the art world has global reach and impact, even as it is dominated by the U.S. market.

Yet as the U.S. has led the world militarily, culturally, and industrially, the choices our government and society have been impacting ordinary lives and livelihoods in ever more unpredictable ways, including through the acceleration of natural forces beyond human control.

Alejandro Pineiro Bello (b. 1990), Tormenta Solar (2023), oil on hemp, triptych, 138” x 228” in the collection of the Rubell Museum, Miami. The Cuban painter, who made a big impression with a breakout show in Miami last December, is currently showing his newest paintings this week with Pace Gallery at Frieze London.

Emanating from a spiral, at whose core lie pure mathematical equations that surface in everything from the Golden Ratio to the music of J.S. Bach, these forces are as destructive as they are creative. And we as humans, whether conscious of it or not, feed into them.

What I keep stressing to those who join me in looking at art together is how I can tune into the frequency of these forces, both natural and man-made, that manifest in life and in art.

Doing this fluently and with a comprehensive view on what matters to people becomes my way of traveling through time and space to arrive at a magnificent and satisfying understanding of art as inseparable from the natural forces of life.

It’s also the name of my company: Charting Transcendence.

What’s Special About Seeing Art in Chicago: a Postmodernist View

A view of a spiraling jetty into Lake Michigan across from Lakeshore Drive from the observation deck of 875 Michigan Avenue (formerly the John Hancock Center).

With the peak of Miami’s art buying season (a.k.a. Art Basel Miami Beach) clearly on the horizon, I’ve been content to not travel as much outside of South Florida lately (and, apart from a few trips to NYC, hopefully not too much more before year’s end.)

I did make a priority of spending several days in Chicago last weekend to participate in Chicago Exhibition Weekend (CxW), a locally sponsored initiative highlighting the city’s vibrant art scene. It is now held in late September / early October as an antipode to EXPO CHICAGO, the Midwest’s largest fair, held in April.

I don’t think any other American city (save possibly New York) gives quite as much quality, prime real estate to art museums and cultural institutions, of which there are (conservatively) dozens of important ones. One might need a day or two to survey the entire Art Institute of Chicago and a week or more to even attempt an overview of the rest.

One current notable exhibition on the South Side commemorates the 50th anniversary of The Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago. I’d call it the season’s “best show in town” for its sheer breadth and diversity, pulling from the museum’s half century of collecting, starting in 1974 when modernism had given way to postmodernism.

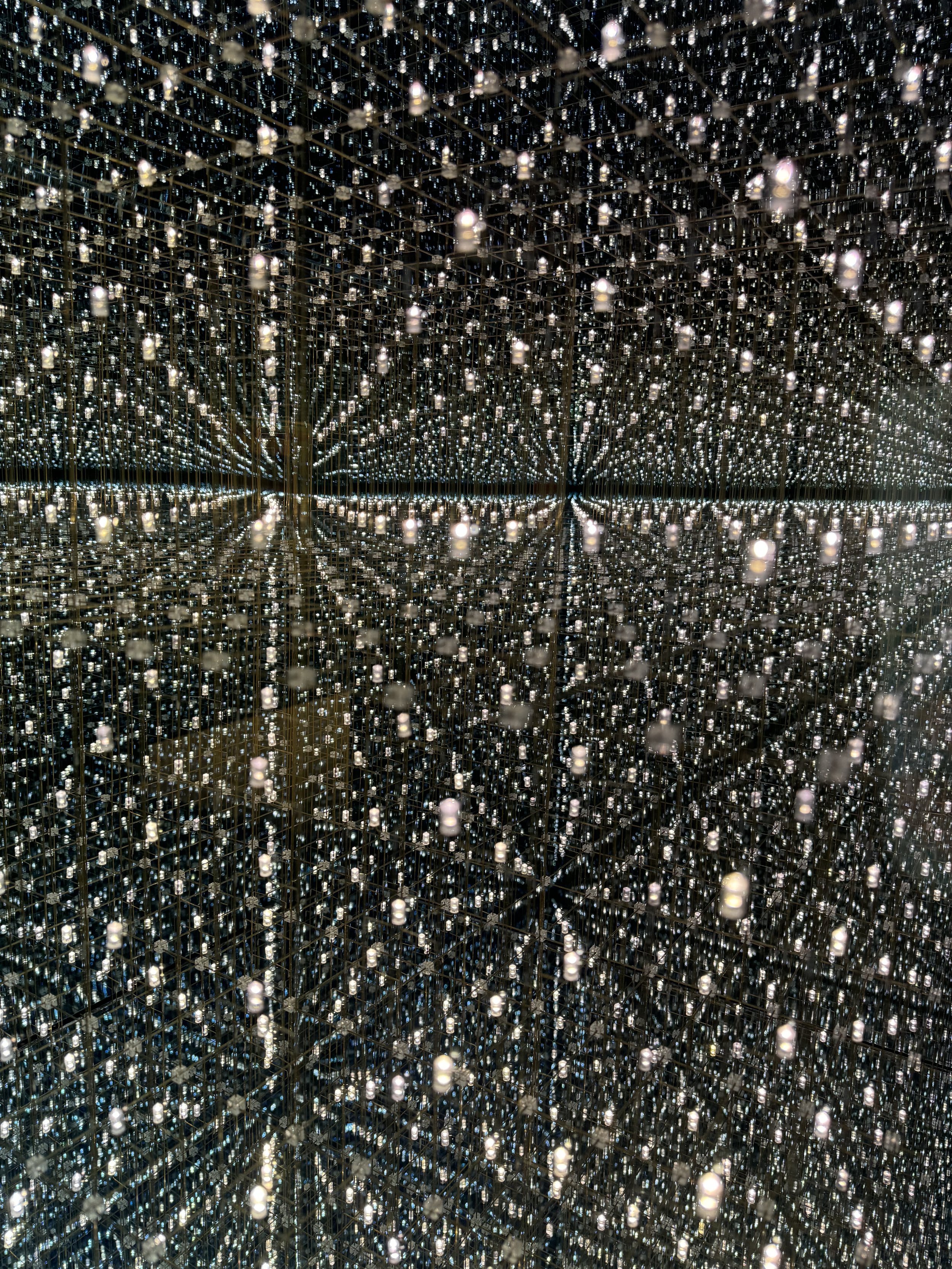

A close-up view of Infinite Cube (2014), mirrored glass with internal copper wire matrix of 1,000 hand-soldered omnidirectional LED lights, was created by Antony Gormley (b. 1950) based off of a concept by the late Gabriel Mitchell (1973-2012), a Chicago artist who suffered from schizophrenia. This unusual sculpture is in the permanent collection of the Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago.

One delightful surprise at the Smart’s 50th Anniversary exhibition was coming across this sculpture by Claudia Wieser (b. 1973), a German artist working in geometric abstraction, whose work I believe to be underrated generally yet highly appreciated by connoisseurs.

Kintsugi is a traditional Japanese art form that mends broken pottery by gilding the shards into unique artworks, generating rich metaphors about imperfection and resilience, demonstrated in this ceramic fragment, epoxy, and gold leaf sculpture, Translated Vases (2007) by Yeesookyung (b. 1963).

This vintage 1966 poster from the University of Chicago’s collection advertises the inaugural exhibition of the Hairy Who, a group of young artists affiliated with the Art Institute of Chicago, working in an irreverent, neo-surrealistic style today known as Chicago Imagism.

What’s even more compelling about encountering contemporary art in the Windy City — once the country’s second largest city and alternate cultural capital — is that it ends up to some degree conflated with the visual aspects and historic development of its architectural landscape.

Below: several examples of 20th century skyscrapers in Chicago, incorporating classical, modern and post-modern elements of architecture, as seen from the Chicago River.

The interplay between architecture and art in Chicago encourages a deeper understanding of how both mediums employ the term "postmodernism” as a concept popular from roughly the 1970s to 1990s. Nevertheless, the term carries connotations distinct in both realms.

Postmodernism in Chicago’s architecture is often characterized by a playful integration of historical references and eclectic styles, emphasizing context-specific visual elements that depart sharply from the boxy nature of modernism (e.g. the styles promoted by 20th century legends Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe).

In contemporary art discourse, postmodernism encompasses a broader ideological shift that challenges established notions of universal truths. It frequently employs mixed media, conceptual frameworks, and an emphasis on viewer interpretation.

Although too complex to summarize in this newsletter, postmodernism in art often serves as a philosophical critique aimed at deconstructing traditional artistic conventions. These features are all hallmarks of many of today’s most interesting works of contemporary art, many of which can be seen on any given day in Chicago museums and galleries.

Located on Chicago’s north side, Wrightwood 659 is a private museum, designed by superstar architect Tadao Ando (b. 1941), worth visiting just to gawk at the architecture alone. An interesting surprise upon entering is Zhang Huan’s (b. 1965) Peace I, modeled after a traditional Chinese temple bell.

One block off of the Magnificent Mile, the Arts Club of Chicago puts on museum-quality shows, including this unusual body of traditional papercut collages by Haegue Yang, a critically-acclaimed South Korean artist who shows with Seoul gallery Kukje.

Kieth (Man with Grill) (2020), by Paul D’Amato, a Chicago photographer whose series, Midway, exhibited at the magnificent Beaux-Arts Chicago Cultural Center is comprised of intimate portraits of residents of the neighborhoods surrounding Chicago’s smaller airport (MDW) on the South Side.

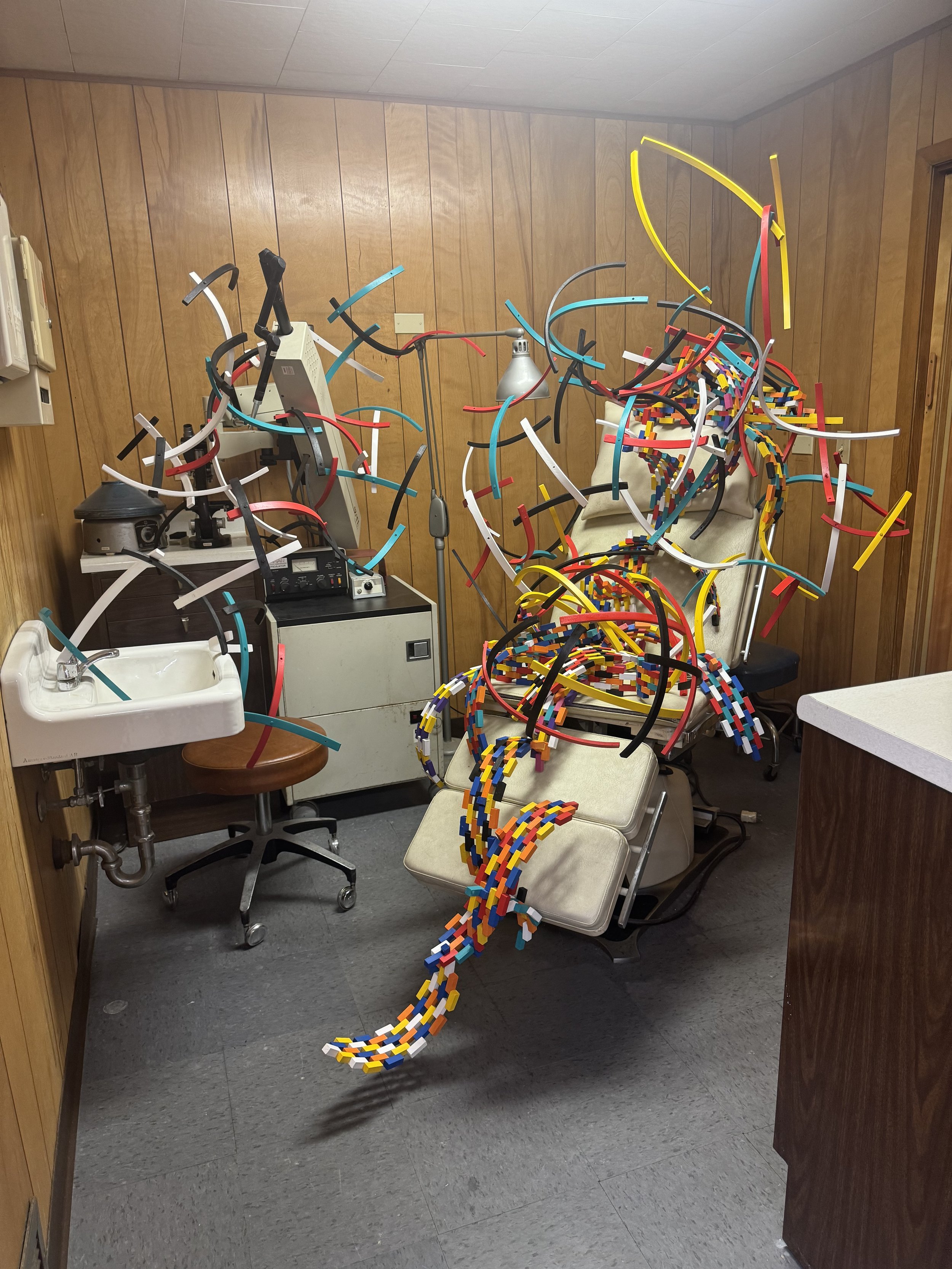

A particular highlight among smaller galleries open during CxW 2024 was this anthropomorphic sculpture by Anita Lim (b. 2004) presented by Brooklyn’s Good Naked Gallery in a vintage 1970s dermatologist’s office run by Patient Info in the Ukrainian Village.

Although the city’s art galleries remain scattered from the North Side across the West and South Sides, the main gallery hub in recent years has coalesced around the West Town gallery district, which stretches a mile or two through West Town, roughly from the West Loop to Ukrainian Village.

As someone who makes an athletic workout of seeing art, I typically manage this circuit equally conveniently on foot, bicycle, or by public transportation, covering half dozen or more of my favorite Chicago galleries in a day.

These include, non-exhaustively and in no particular order: GRAY, Rhona Hoffman, Kavi Gupta, Corbett vs. Dempsey, SECRIST | BEACH, Mariane Ibrahim, and Monique Meloche. All regularly show work at fairs both nationally and internationally and are outstanding places to learn about artists with particular appeal to Chicago collectors (e.g. the Chicago Imagists) or Chicago-born artists with international superstar appeal, many of them artists of color such as Nick Cave or Theaster Gates.

Jamaican artist Leasho Johnson (b. 1984) explores the intersection of Black queer identity, Caribbean folklore and post-colonial narratives with a new body of work at Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, a prominent Chicago gallery with outposts in Paris and Mexico City.

Greg Breda (b. 1959) is a self-taught Los Angeles-based painter who takes a delicate and contemporary approach to the popular genre of Black portraiture. He is currently showing with Chicago’s Patron Gallery, based in the West Town gallery district.

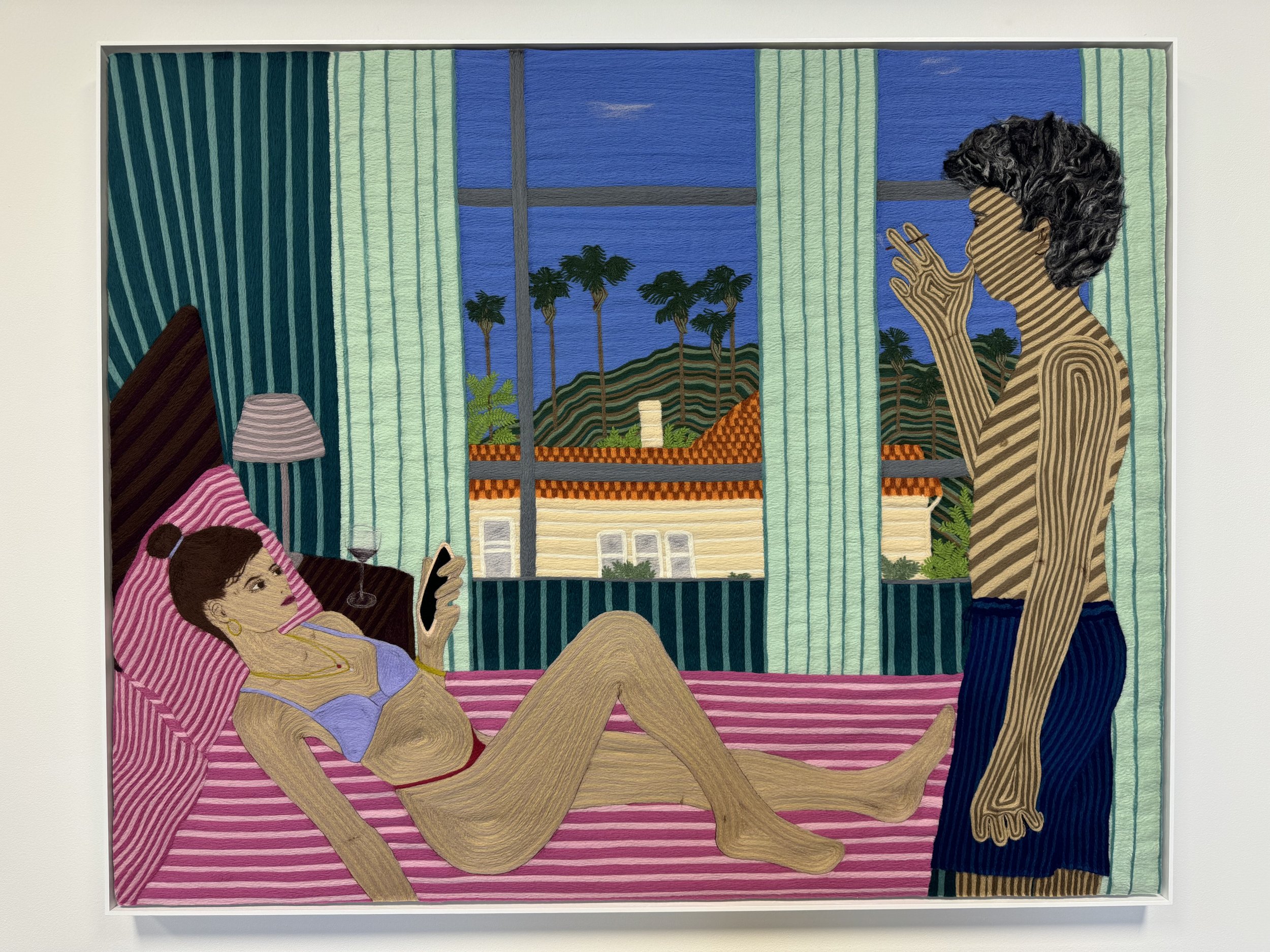

Cheryl Pope (b. 1980) has innovated a unique needle-punched wool technique of assemblage that resembles painting but is, in fact, thread-based. In addition to her show at Monique Meloche, she currently has an appointment-only show on in Los Angeles at Easy Does It Curatorial Space.

Domestic forms clash with postmodernist visual references to African diaspora art in this neo-surrealist sculpture by African-American artist Willie Cole (b. 1955), on display at one of Chicago’s finest contemporary art galleries, Kavi Gupta. Given its rich references, Willie Cole’s work is widely collected by major art institutions these days.

A Bonus from the Archive: Two Photographs of Modern and Postmodern Means of Conveyance About Chicago

Joseph Wolfe, great-grandfather of the author of this newsletter, in the driver’s seat of an unidentified model convertible on the South Side of Chicago, Summer 1929. Given Wolfe’s modest salary as a police officer during Chicago’s heyday of Prohibition and the Al Capone era, it is fair to speculate on the lore of cooperation between the Windy’s law enforcement officers and gangsters in the 1920’s.

Author of this article — not quite yet a Chicago gangster, but an art advisor in the making — riding the CTA bus to visit galleries on the North Side of Chicago, Fall 2019, the year after completing his degree at New York’s Sotheby’s Institute of Art. The ability to weave diverse threads into a comprehensive narrative about consciousness in art is what distinguishes Charting Transcendence from traditional art advisories.