A Home Run Story

A Triangular Train of Thought and Consciousness

Straight off the bat, let me demonstrate how I lead those working with Charting Transcendence on an adventure in creative storytelling.

ALL ABOARD as we embark on a circuitous journey across half the country, starting with a bit of simple geometry, leading into a comparison of modern and contemporary art, and ending up musing about a home run and Mozart at a baseball game in Miami.

Whether you’re looking to learn more about art or simply get to know yourself better, follow along as I map a route of consciousness (while throwing in a bit of magic for good measure.)

This what I do every day — after all — encountering art and deploying my gifts and passions in service of those around me through the creative engine of Charting Transcendence.

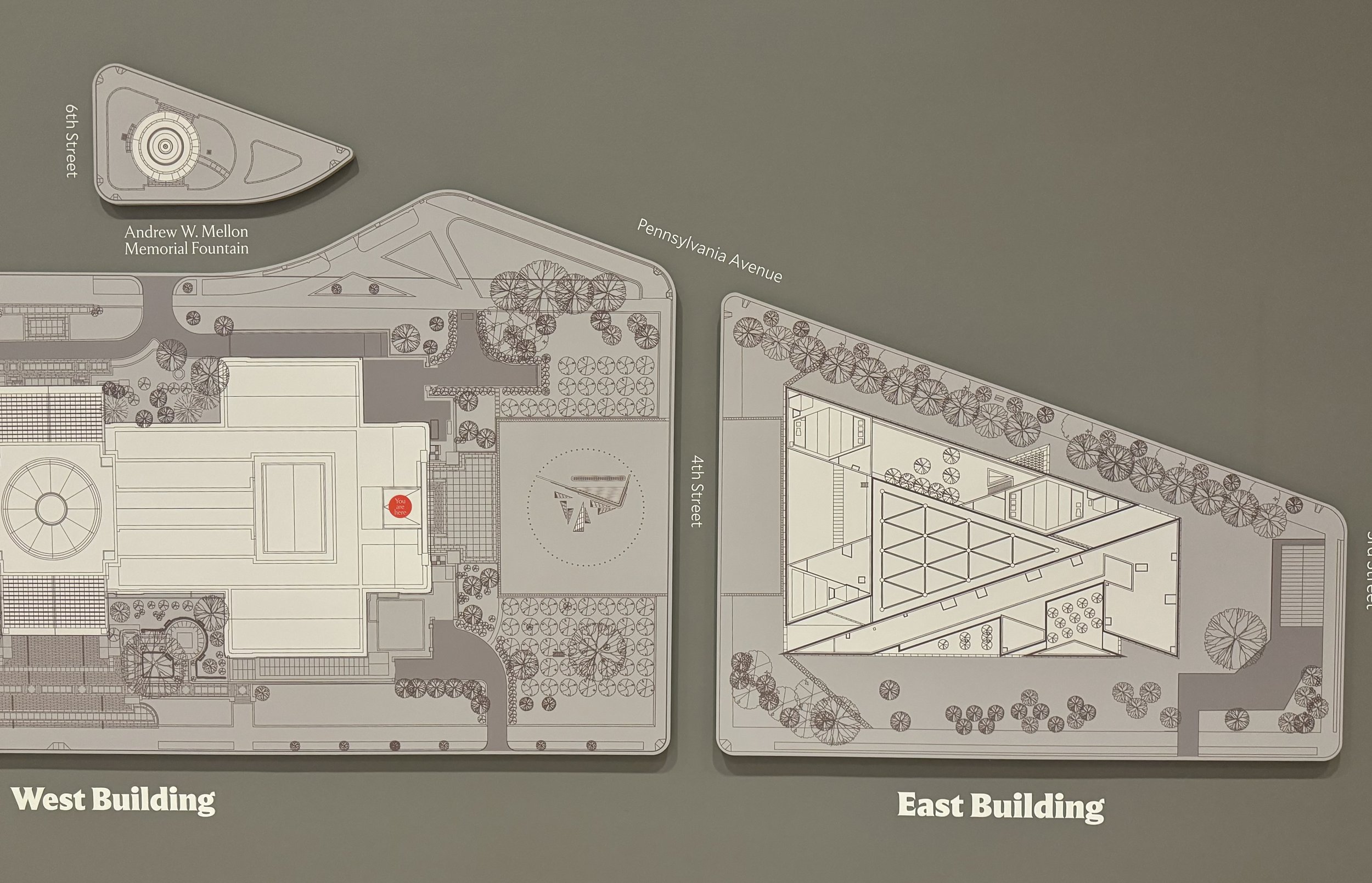

I.M. Pei (1917-2019) was a Chinese-born architect who emigrated to the United States. Above is a rendering of his initial esquisse of the East Building and, below, a birds-eye diagram of both wings of the National Gallery of Art today. Note how the original square West Building elegantly gives way to a set of simple overlapping triangles via a circle abutting the street dividing the two.

A New Train Route Triangulates Chicago with Miami via Washington

Amtrak recently announced The Floridian, a brand-new, 47-hour-long train route obliquely connecting Chicago to Miami via Washington, D.C., leaving some train enthusiasts on the internet pondering the need for the triangular detour.

Born in Washington and trained as a career diplomat, I have spent many years of my life on the road, and on the go: a surveyor of broad cultural, emotional, and psychological landscapes.

What’s more about me: stereotypically of males who fall on the autism spectrum, I have been fascinated by trains since childhood.

As opposed to how I typically travel by plane, I find something supremely comforting about the stability, regularity and constant stimulation trains provide through both their gentle rocking motion and broad windows on cities and landscapes.

One of the happiest days of my life came the Christmas I turned seven when Santa Claus left me a vintage Lionel train set under the tree, and the rest — as they say — is history.

By the time I was in my early 20s, I had eagerly crisscrossed rails across swaths of Europe and Asia, captivated by the changing scenery and engrossed by learning and adventure along the way.

So, naturally, I was delighted when I learned this week of a new direct train between Chicago, where I previously lived, and my current home in Miami via my hometown, a city majestically blessed with art.

The East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., a highlight of Charting Transcendence’s recent art tour, showcases in its atrium (left to right) 20th century American art by David Smith, Alexander Calder, and Ellsworth Kelly.

Coincidentally, I’m just about to have touched base with all three cities within a fortnight, with museum tours in Washington the week before, studio visits in Miami this past week, and a slew of gallery openings for Chicago Exhibition Weekend on deck next.

So, I figured, for this edition of my newsletter, why not let this triangulated journey between the Windy and Magic Cities conjure up a poetic narrative demonstrating how I situate discovery, art and culture within a broader context?

Although I personally won’t spare the time for a 47-hour one-way ride from Florida to Illinois anytime soon, I do cherish the route map its schematic provides: a train of consciousness that keeps taking me places.

At the Junction of Modern and Contemporary Art

Lipstick, Lip Gloss, Hickeys Too (2022) by British artist Flora Yukhnovich (b. 1990) exemplifies a flavor of highly sought-after abstract contemporary art, co-curated with 100 years of modern art from the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s Hirshhorn Museum, its splotchy colors hearkening back to classical French painting in the style of Jean Honore Fragonard (1732-1806).

Charting Transcendence’s art tour in Washington, D.C. on September 19 covered the highlights of the East Building of the National Gallery of Art as well as an outstanding group show at the Hirshhorn Museum.

A veritable “home run” of the Washington’s museum season, Revolutions: Art from the Hirshhorn Collection, 1860–1960, brilliantly blends the evolution of modern art from the Industrial Revolution to the Post-war era, sprinkling in many contemporary artworks adored by today’s most sophisticated collectors.

There is a relatively delineated yet still somewhat nebulous distinction between art we might define as modern versus contemporary that brings the meaning behind the Hirshhorn’s juxtaposition of its collection’s old and new art into clear focus.

In short, the age of modern art starts somewhere mid-19th century just before the dawn of Impressionism with painters like the Frenchman Édouard Manet (1832-1883), who fundamentally reimagined how subjects were depicted, although some scholars may even point back further towards the Spaniard Francisco Goya (1746-1828) as being the first of the Modernists.

Boob Wheel (2019) by Loie Hollowell (b. 1983) blends sacred geometric abstraction into voluptuous, multidimensional feminine figuration. Private collectors have recently paid premiums at auction for contemporary works like these.

A delightful mid-century composed fish sculpture by Spanish legend Joan Miró (1893-1983) hangs from the ceiling of the Hirshhorn’s gallery, presaging the contemporary era’s voracious predilection for mixed-media art of all sorts.

Typical of the historic gender imbalance in the visual arts, the abstract expressionist sculpture of Dorothy Dehner (1901-1994) was for decades largely overshadowed by that of her one-time husband, David Smith (1906-1965), making her work’s inclusion in the Hirshhorn’s show a deeply satisfying discovery for Charting Transcendence.

The curation of legendary Miami outsider artist Purvis Young’s (1943-2010) painting in the Hirshhorn’s show’s mashup underscores how artists from underprivileged backgrounds have bridged modern and contemporary styles of painting.

What we today call contemporary art, on the other hand, evolves from modern art anywhere from around 1945 onwards through the end of the 20th century. Usually, the distinction lies not so much in the date the art was created, but in the style and influences that provided for it.

By the 1940s-1950s, much of avant-garde art had become so abstract that it provoked a reaction leading to Pop, Conceptual, Minimalist and Postmodern art, approaches that, in my mind, sit pretty clearly on the contemporary as opposed to modern end of the spectrum.

Nevertheless, no one observer can necessarily categorize all abstract art of recent years as either modern or contemporary: at some point in between, the distinction is moot.

That being said, my training and practice as a connoisseur helps me appreciate the interplay between these two overlapping categories, which is what made the Hirshhorn’s show so enlightening for both my guests and me.

In short, the Hirshhorn show nailed a survey of a century and a half of modern and contemporary Western art in one fell swoop.

And although art-spectating in Washington is still a minor-league affair on most days compared to the same in New York, London, or Paris, as a native Washingtonian I can say that there is no more appropriate detour to make than the junction of modern and contemporary art apparent at the Hirshhorn’s show, which runs through April 2025.

Patriotism of different eras is evident in this iconic 1918 flag painting by Childe Hassam (1859-1935) (right) paired with a set of photos (left) shot by Catherine Opie (b. 1961) at President Obama’s first inaugural in 2009.

Painterly approaches to human portraiture and representation across 150 years of modern society contrast in the juxtaposition of paintings by (left) Amoako Boafo (b. 1984) and (right) John Singer Sargent (1856-1925).

Texture, color, and geometry clash in provocative ways in this pairing of a painting by Synchromist painter Stanton MacDonald-Wright (1890-1973) and mixed media by contemporary Native American, rising-star artist Dyani White Hawk (b. 1976).

A digitally edited photograph from Paul Pfeiffer’s (b. 1966) Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse series is flanked by a ringside depiction of a boxing match (right) by George Wesley Bellows (1882-1925), highlighting the aura and allure of sports in American culture.

Back Home in Miami, an Encounter with Genius: Baseball’s Mozart

I rarely go to sporting events; in fact, for me, just following sports tends to veer towards cultural overload.

After all, already my brain is oversubscribed on bandwidth for contemporary art, music, or politics, and I concede that this sets me apart from most of my friends and family, foremost my father and sister who are die-hard fans of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

But the night before I left Miami for Washington, I did make it out to Little Havana’s LoanDepot Park, where the Marlins hosted the league-leading and perennial World Series favorite Dodgers for the first night of a three-game series.

A few innings in, I saw L.A.’s top pitcher and batter Shohei Ohtani hit a spectacular home run.

Robert Vargas, L.A. Rising (2024), a mural of Dodger’s superstar Shohei Ohtani (b. 1994) that debuted on the side of a hotel in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, earlier this year.

Most people who know baseball understand that it’s not often that a pitcher can bat very well, much less can a batter expect to ever seriously pitch.

Yet Ohtani’s statistics on both sides of the mound are exceptional: in fact, just two nights later he became the first MLB player to hit 50 home runs and steal 50 bases in one season.

Many have commented on his exceptional athletic prowess and range of ability. Some compare him to Babe Ruth (1895-1948): a legend of the ages - or at least a once-in-a-century manifestation of greatness. (The market appears to recognize this - no wonder Ohtani’s contract is valued at $700 million.)

My connoisseurship of genius would lead me to believe Ohtani is to be of the same caliber as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), an all-around virtuoso, capable of layering breadth and complexity of skill on in gobs as he did, for example, in his masterpiece Symphony No. 41 in C “Jupiter,” his late operas, or a dozen other things he wrote.

Forgive me for triangulating, for perhaps it’s just my autistic brain sketching out a conceptual map of some sort, but I suspect that had I not spent that evening watching a baseball team from Los Angeles play in Miami would my train of thought have so circuitously led via some musing about trains and classical music to the conclusion of this newsletter.