How to Map Your Own Good Taste in Art

Minneapolis’s downtown lies in the background of this geometric sculpture by American minimalist artist Sol Lewitt (1928-2007), sitting on the rooftop of the Walker Art Center, one of the best contemporary art collections in the country.

Why Building Your Own Map of Good Taste in Art is Important

Charting Transcendence is a new kind of art advisory that I’ve been building methodically and organically — and with tremendous passion — through a broad network of relationships.

The company’s name reflects my vision of tracing a unique path through a contemporary world of art, culture, and beauty, and my goal is to help clients do this themselves, creating meaning and connection out of art experiences.

Yet the world of art is more heterogenous and saturated with stimuli than ever before: try as one might, no one can see “all of the art,” nor should one even dare attempt to, lest one quickly become overwhelmed and exhausted.

An article in the Financial Times notes a recent trend: people of ample means and interest in acquiring fine art are frequently outsourcing their choice of taste to either interior designers or art advisors who curate works based on what they decide is trendy or acceptably “good” art.

Now, I do not mean to say that interior designers aren’t important in envisioning what should hang above your sofa, whether it costs $5000 or $30,000 or more; rather, I’m questioning the notion of who decides what is good.

Taste in good art was once acquired as a matter of course, a sine qua non for successful, educated individuals. But nowadays, too many forms of cultural diversion have crowded out the field. On the art market alone, too many galleries offer too many different kinds of art (much of which, unfortunately, is not very good).

It is a full-time job to stay abreast of the choices made by curators and collectors that reflect the complexity of modern life. Therefore, pragmatically it makes sense that modern collectors often don’t have or take the time to learn that people once did.

But the solution shouldn’t be the total outsourcing of taste, which not only is infantilizing; it also leads too many collectors to miss out on what could be a deeply satisfying and revealing personal journey.

Charting Transcendence is an art advisory that intuitively crafts such journeys for collectors through keen observation and deep introspection on the things that matter in life: art that leads to profound moments of transcendence and awe.

What’s Hot: Geometric Abstraction in Fiber Art

Work by two fiber artists, Tia Keobounpheng (top) and Regina Jestrow (bottom), both previously mentioned in editions of this newsletter, with innovative practices that reflect important and fashionable trends in contemporary art today.

Collectors and curators, both institutionally and privately, have lately taken keen interest in art that is rooted in craft traditions.

Foremost among these are thread, fiber, or textile art, domains that often have been relegated to artisans and women, who for centuries were generally not taken seriously as fine artists. Such work was sorely underappreciated, undervalued, dismissed as something that’s not quite art… or even ignored.

Although much remains to be done in order to address gender inequality in the arts, generations of women artists, many of whom are now finally becoming recognized as being some of the greatest and most valuable of our time, have managed to successfully erode this shameful standard.

I can cite quite a few examples of really good art that’s gained attention, including the women quilters of Gee’s Bend and the Pattern & Decoration movement of the 1970s, Furthermore, recent exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Jorge M. Perez's El Espacio 23 Collection in Miami have provide ample proof of this popular and significant trend.

Everywhere you look, in fact, galleries and museums are telegraphing that colorful and geometrically abstract work of all kinds is very much in style. But why is this?

One possibility suggested by close observation of this year’s Whitney Biennial is that such works provide a welcome respite from heavier and more politically charged content, all too common in an election year like 2024.

Therefore, in recognition of what I feel is important and very good art, I’d like to highlight below two strong and innovative practices in thread-based geometry by two exceptional women artists whom I now have the privilege of calling friends.

Tia Keobounpheng: Weaving Threads of Consciousness into Sacred Geometry

Tia standing in front of her commission for the University of St. Thomas (St. Paul, Minnesota), FOUNDATION No8 (2024). Tia executed this 10’ x 20’ work by hand, over six months, using only pencils and colored pencils. The subtle irregularity of her hand’s pressure exerted on the wood melds exquisitely into the perfection of the geometry.

Conceptually, I unweave my identity and break apart the methods of traditional women’s work in order to present fiber as Abstract Art… Rooting my work in geometry, I draw connections between the living world and measurable natural order… I use geometry to move my consciousness beyond binary narratives, in order to imagine a more complex framework of understanding… Looking beyond the human systems that we impose upon life, I use a visual language to imagine an existence that celebrates interconnected complexity and expansive diversity. —Tia Keobounpheng

Every now and then, I come across an exhibition in a museum or gallery that floors me, and I simply cannot stop thinking about it.

Last September that show was Tia Keobounpheng’s Revealing Threads at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Almost never do I see abstract art with such intense vibrancy and energy as the large thread-on-wood pieces exhibited there.

Several weeks later, I spoke with Tia, and having already sold several of her pieces to collectors in Charting Transcendence’s network, I asked if I could pay her a studio visit on my next trip to Minneapolis.

Trained as an architect and with a long background in craft (together with her Laos-born husband she has run a small-batch, custom jewelry studio for nearly 20 years), Tia has been fully focused on her fine art practice since 2021, making the fact that museums have already started collecting her work even more impressive.

Tia's practice is conceptual to the degree that when she creates these artworks, she enters into a deeply reflective state of creative consciousness, little if any of which is necessarily apparent to the viewer but is 100% relevant to the result.

Tia launched headlong into her fine art practice in 2021 as she helped her 4th grade child with pandemic-era remote geometry lessons. Early experiments in threading colorful patterns quickly developed into one of the most interesting contemporary fine art geometric abstraction practices on the art market today.

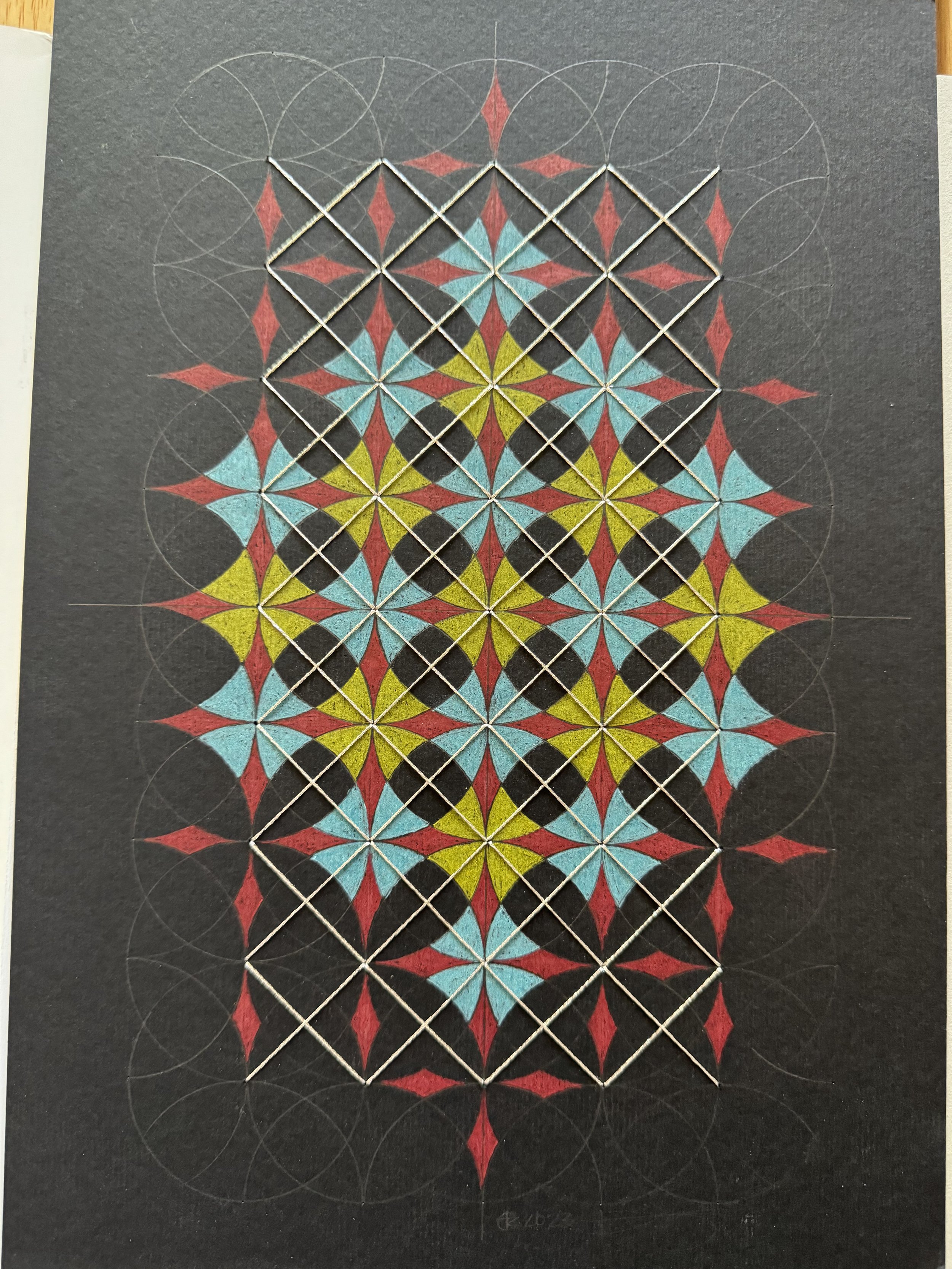

FOUNDATION No7 (2023) pencil and colored pencil on wood," 8x“8 , an intriguingly beautiful artwork available from Tia Keobounpheng. The artist’s hand is made visible through variations, resulting in minor imperfections that, when viewed up close.

INTEND No2 (2023) pencil, colored-pencil, metalic-thread on A4-sized paper, available for purchase from Tia’s studio (please contact Charting Transcendence for details).

Detail of a new thread on board work in progress in Tia’s studio. Now sought after by major collecting institutions, this piece is expected to be shown in New York City in the spring of 2025.

Her exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art underscored how, as she went through iterations of weaving her geometrically complex designs, she was in fact reflecting deeply on her family's origins, uncovering a hidden "thread" of European indigeneity in her blood line.

Raised in a Finnish-American household in northern Minnesota, Tia recently discovered that one of her ancestors was actually ethnically Saami (Laplander), and this identity had been repressed due to generations of domination by Russians, Swedes, and Finns.

Thus Tia's work results out of a thoughtful and explorative exploration of complex personal narratives. And although her patterns resemble those found in indigenous societies, she says that the methods she uses are as disconnected from traditional techniques as she has been from the hidden threads of her own bloodline.

For what it’s worth, I will note that one important private art museum in Miami, the Juan Carlos Maldonado Collection, demonstrates through its exhibitions that geometric abstraction is a universal movement that transcends geographies and cultural backgrounds. This would suggest that sagrada geometria or sacred geometry is encoded in the very fiber of our beings, through the language of the universe — mathematics.

Tia Keobounpheng is a phenomenal artist who intuitively understand this sacred thread, creating beautiful fine art objects that are unlike any others available on the art market.

THREADS no9 (2023) a massive 72" x 48" thread and colored pencil on wood piece that now hangs in her home studio, was one of the highlights of Tia’s breakout show at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Other large pieces have been acquired by institutional collections in the Midwest, including the North Dakota Museum of Art.

Subtle irregularities in pencil pressure create deep and satisfying meaning when admiring the regular geometry of FOUNDATION No9 (2024), recently sold to Austin, Texas-based collectors in the Charting Transcendence network.

Front and back of INTEND No 6 (2023), thread, pencil, and colored pencil on paper board, available for purchase from Tia’s studio through Charting Transcendence.

Tia’s patterns are evocative of geometric designs seen in various world cultures while entirely her own creation.

Everyone of a certain age remembers the song Closing Time, by Dan Wilson and the 1990s era band Semisonic, so it’s worth pointing out that Tia’s artwork from her Circle Round series adorns the cover of their latest album Little Bit of Sun (2023).

Regina Jestrow: Sewing Venerable American Traditions into Cutting-Edge Contemporary Art

Regina Jestrow, Pieced Landscape 46 Tempest (2024), hand-dyed cotton (reactive dyes), gifted curtain, thrifted sequin fabric, muslin, felt, and thread. The latest in the artist’s body of work of contemporary fine art quilting, this piece is available for purchase directly from her studio.

My practice explores the reinterpretation of American quilting traditions by investigating textile history and geometric pattern symbolism… I draw inspiration from the vibrant natural landscapes of South Florida, weaving the colors, textures, and structures of the region into my work using a diverse palette of new, second-hand, and hand-dyed textiles. An integral part of my artistic ethos is consciously incorporating thrifted and second-hand clothing and fabrics. By doing so, I aim to reflect Miami's culture and address the pressing issue of textile waste plaguing our society. —Regina Jestrow

Living in Miami I have had the pleasure on several occasions of visiting the home studio of an artist whose work beautifully reflects America as a contemporary patchwork — both traditionally and literally.

This is because America’s cultural fabric is deeply rooted in craft. On today’s contemporary art scene, this manifests in paying homage to unsung artists in particular, such as the African American women who create the Gee’s Bend quilts and log cabin patterns of the 19th century. (Intersections such as these, by the way, are generally good indicators of art that matters these days,)

Regina’s art does all of this but with a contemporary twist, reflecting her own intercultural background. Born and raised in an Italian-American household in Queens where her mother made her own clothes, Regina later moved to Florida, where she is now an integral part of the multicultural mix of artists that makes up Miami’s dynamic art scene.

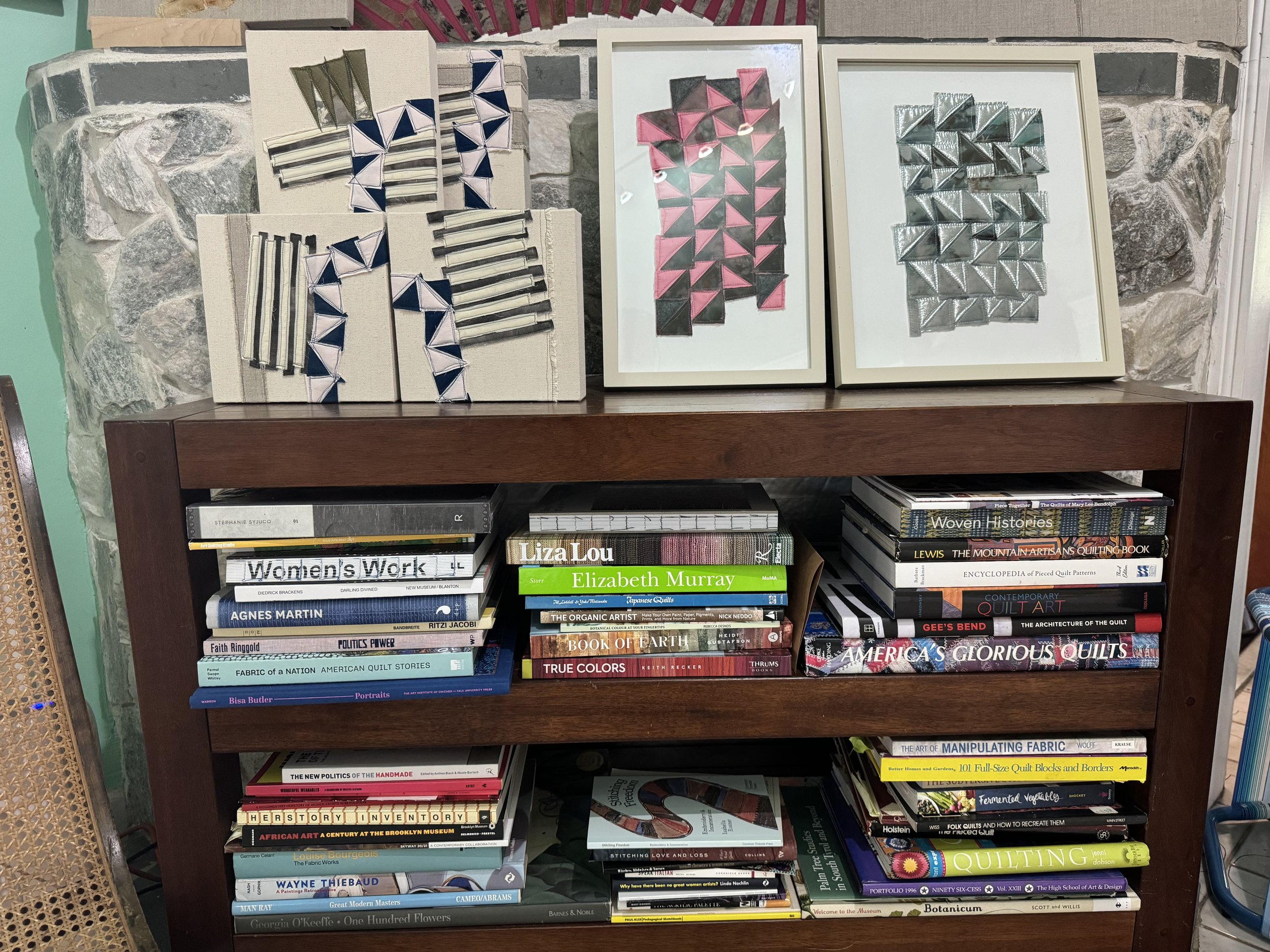

Swatches of various fine art quilts hanging on Regina’s Miami studio wall reveal the visual and material diversity of her approach to the traditional craft medium of quilting.

Regina’s artistic influences, on display on her studio bookshelf, meld a deep understanding of craft and Postwar Contemporary art into a practice uniquely her own.

This fabric hanging in Regina’s studio has been dyed using inventive ice-bath and Japanese shibori knot-tying techniques that Regina has taught herself. She then takes this magnificent fabric and cuts it in strips to incorporate into her quilted pieces, which can be framed or hang directly on a wall.

Regina Jestrow, Pieced Landscape 35 (Cypress Dome in Double Fire Pattern), 2024 hand-dyed cotton (reactive dyes), men's shirts, muslin, batting, thread, felt.

For years Regina has turned to thrift stores to acquire colorful and eclectic textiles and materials, often distressed by wear and tear and cigarette burns, to cut up for use in her fine art quilts. Friends also gift Regina swatches of fabric and material to work with (she’s even experimenting with strips of cowhide).

Even a luxury French interior design salon, Liaigre, has provided her with materials that she will use to make pieces for display at their showroom in the Miami Design District — an auspicious mark of her work gaining recognition for its excellence and potential to be curated in beautiful homes.

Regina’s most recent museum show in Key West, Florida, Vulnerability and Resilience, convinced me that she is making important artwork that is not easily found elsewhere — and certainly not at the very reasonable prices that she sells them for.

I will note that I have seen some outstanding museum and gallery shows about quilts in recent years, especially Pieced & Patterened: American Quilts ca. 1800-1930, shown in 2021 at the St. Petersburg Museum of Fine Arts, as well as the 2018 Metropolitan Museum of Art show History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift.

This goes to show that quilts are meant to be taken seriously as contemporary fine art in America. They substitute well for abstract expressionist-style paintings, especially at larger sizes, while adding rich texture to interior design.

Moreover, Regina’s unique approach as an artist in the southernmost major American metropolis situates her within deep traditions of craftswomen, whose contributions to the American cultural fabric are now celebrated more visibly.

Pieced Landscape 51 (Kintsugi Pinwheels) (2024), interstitched with strips of golden fabric, refers to the Japanese artisanal practice known as kintsugi, by which broken shards of ceramic are gilded in a act of meticulous repair.

Pieced Landscape 40 (Mangos at Midnight), (2024) hand-dyed cotton (reactive dyes), gifted ribbon and vinyl, repurposed chino pants, muslin, felt, and thread (40” x 88”) has an almost cinematic quality unprecedent for a “quilt” and is available for purchase.

Irregularity interspersed with triangles (one of the most productive geometric shapes in Regina’s practice) is a beautiful feature of Regina’s Glitter & Gold 12, (2023), reclaimed pencil-skirt, vinyl tote bag, thread, felt, batting 38” x 35”.

Americana Quilt 75 (2022), assorted fabrics, hand-dyed fabric, thread, muslin, stretched on wooden supports, 41.25 x 88.25 x 1.5 in, is available for purchase from Regina’s studio.

Lastly, Some Favorite Art Spotted in Twin Cities (Minnesota) Museums

Star Cage (1950) by David Smith (1906-1965), in the collection of the Frank Gehry designed Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota. Alongside Alexander Calder, who is a household name for his mobiles, art historians generally consider Smith to be the greatest American sculptor of the twentieth century.

Multiple examples of geometric abstraction in art are on view at the encyclopedic Minneapolis Institute of Art, including Geometric (2014), a felt tip pen and metallic pen on paper drawing by Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (1922-2019), probably one of the most celebrated Persian women artists of the twentieth century.

Minneapolis’s outstanding Walker Art Center currently hosts the major Keith Haring retrospective, Art is for Everybody, previously shown at The Broad in Los Angeles. The most comprehensive show of Haring’s work in a generation featured rare works like this poignant, 1989 Unfinished Painting, executed just a year before the artist died of AIDS.

Lastly, this lovely piece by Nancy Ariza, Sangre Piteada 2 (2024), woodcut print on cotton fabric, caught my eye on display at the Minnesota Museum of American Art in St. Paul.